Mapping Opportunity: A New Take on Intergenerational Mobility

By Justin Walker

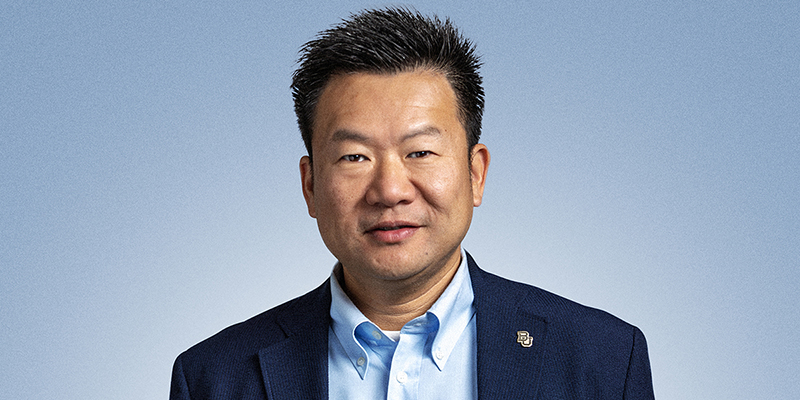

The American Dream has meant different things for different people. But in many cases, it stands for a sense of potential positive intergenerational mobility, said Associate Professor of Economics Zachary Ward, PhD.

“Intergenerational mobility answers whether it matters if you have rich or poor parents for your lifetime outcomes,” Ward said.

Historically, research in this area has found that societies with relatively high mobility are societies where it does not matter if your parents are rich or poor, he said. This is the story that is told of the United States during the 19th and early 20th centuries, sometimes dubbed the golden era of mobility. However, Ward had issues with the way these studies were structured.

“It was always interesting to me the way people put data together and tried to estimate this,” Ward said. “They are doing it in specific ways that were very unsatisfactory to me.”

The most frustrating aspect of prior datasets for Ward was that they often focused on specific populations—mainly white individuals. He felt it was a massive omission to only study the social mobility of white people, especially when equality of opportunity was not that high for all groups within the U.S. for many years.

Ward set out to establish a more encompassing dataset that would cover mobility trends in the U.S. with greater accuracy. Using publicly available and digitized census data from 1850 to 1940, Ward created algorithms to generate family trees, similar to genealogy websites Ancestry.com or Family Search.

“You end up with a dataset that has millions upon millions of family trees for individuals,” Ward said. “You can observe the parent’s occupation and then, 30 or 40 years later, what occupation their child held. This is how you estimate whether it matters if you have a rich father or a poor father in a consistent way over a longer time horizon.”

Ward’s research in American Economic Review shows that over the course of 200 years, intergenerational mobility improved, meaning it mattered less and less if your parents were born rich or poor. However, Ward said, the U.S. still faces many barriers to upward mobility in various places and groups.

Location plays a significant factor in mobility today, Ward said. In rural areas and more impoverished neighborhoods, children tend to have lower incomes as adults, even when considering the parents’ income. Other factors include race and gender.

“There are a lot of things that matter,” Ward said. “There are a lot of other things that could potentially limit the child from achieving their full potential.”

Ward believes this line of research aims to uncover the factors that impact mobility and thus can improve the outcomes for future generations.

“We need to ask, ‘What are those barriers?’” he said. “‘How can we alleviate those things?’ I think that’s going to be a fruitful area of research for the future.”

With this research, Ward hopes studies on mobility will be more encompassing to understand the situation better. From there, researchers and policymakers might identify what policies to enact to improve mobility across the board. But that can only be done with the correct dataset, he said.

“The point of my paper is that if you are trying to figure out where our places of opportunity are—as well as the places with much less opportunity—you need to measure it correctly,” he said.