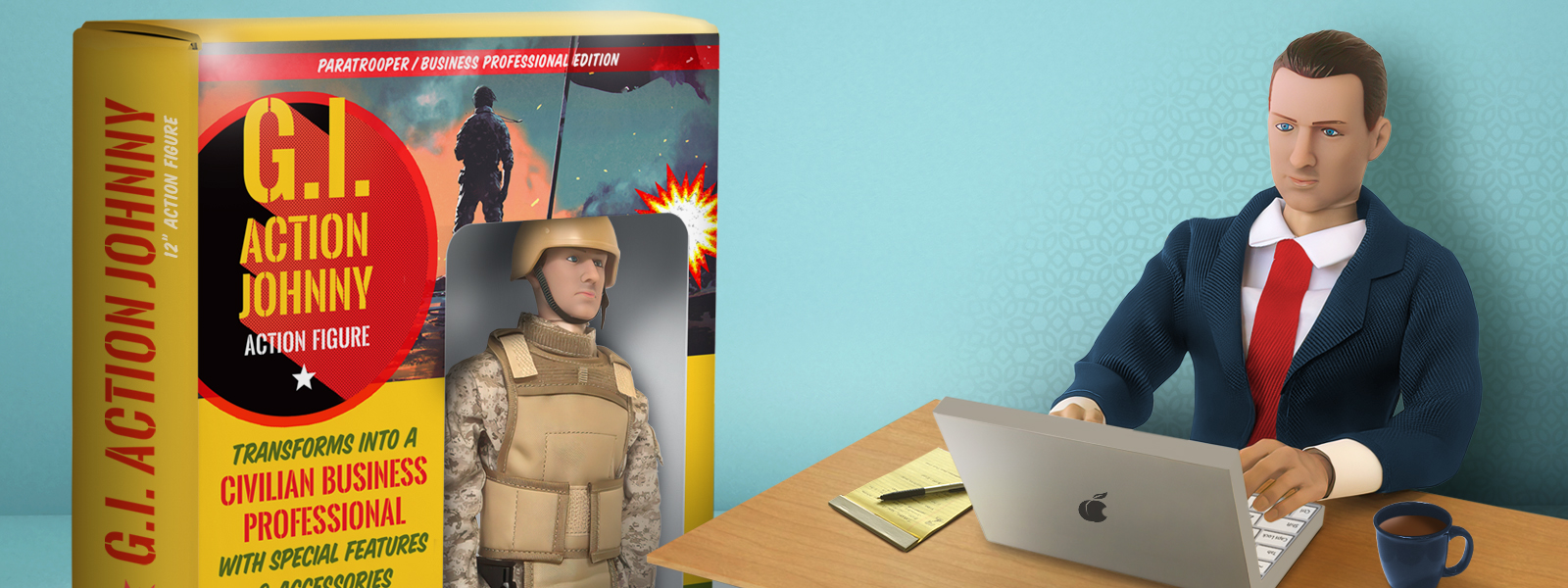

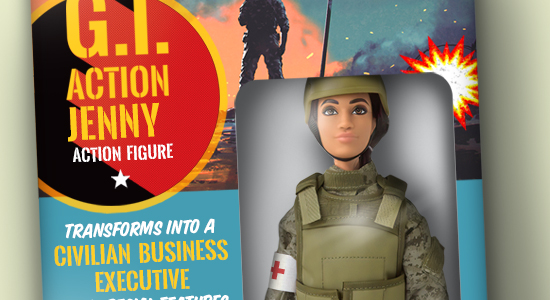

Ready for Action

Armed with unique skills developed in the service, members of the military are bringing a wealth of know-how to the business world

By Kevin Tankersley

For many veterans making the shift from the military to a civilian workplace, it is not the actual hard skills they learned while serving that makes them good employees. Instead, it is all those other things they picked up along the way that help make the transition a smooth one.

After all, there are not many civilian jobs that require employees to fly a fighter jet or engage in artillery combat, but the challenge that veterans often face is how to explain to a hiring manager that those skills can translate to a non-military job setting.

Helping the nearly 100 veterans who are students at Baylor make that change is the primary role of Kevin Davis, a program manager of Veteran Educational and Transition Services (VETS).

He said that his job is “taking the big Baylor mission—to educate men and women for worldwide leadership and service and building strategic resources and community—to effectively transition our military-connected students to this calling outside of the military, recognizing and validating that these unique students have already lived this calling during their military service.”

“You have got these 18- to 22-year-olds who were in charge of equipment worth millions of dollars and sometimes even human lives,” Davis, who has overseen VETS since 2016, said. “How do we take all that awesome experience and translate that in a way that an employer is going to understand it?”

A soldier who was in the infantry, for example, might not think that particular job skill translates into any other field. Davis, however, disagrees.

“You were planning out routes and navigation patrols,” he said. “You were thinking logistics, you were thinking management, how you’re leading your team through this. There are a lot of skills—on a profound level—that you deployed in order to do that effectively. Let’s find that common language that is going to resonate with that employer.”

Davis joined the Marines after graduating from Lewis-Palmer High School in Monument, Colorado. He served four years and then earned a psychology degree from Baylor in 2012. He said that veterans leaving the service often face three significant losses—the loss of community, the loss of structure and the loss of identity and purpose—and his office works with student veterans to address all of those.

With the military being such a mission-focused organization, veterans transitioning into companies or non-profits where the mission isn’t as clear or emphasized often face challenges, said Forest Kim.

“Every organization, of course, has a mission and I have had peers that went out, took a job, but did not feel that sense of esprit de corps—did not feel that strong sense of mission,” he said. “In some (organizational) cultures, for some people, it was just a job. It was not strongly tied to a sense of intrinsic motivation.”

Kim is a clinical associate professor in the Department of Economics at the Hankamer School of Business and serves as the program director for the Robbins MBA Healthcare. He spent about half of his military career as an administrator at large Army hospitals. Kim earned a PhD from the University of Washington along the way and was director of the Army-Baylor Health and Business Administration Program before retiring as a lieutenant colonel from a 22-year Army career. In 2013, he deployed to Afghanistan for six months and served as a military medical training advisor and did some gratifying work, he said.

Decoding the civilian hierarchy

Kim said that some of his peers who landed in organizations that lacked a strong purpose often later went to work as a civil servant or contractor, doing similar work, “just not wearing the uniform.”

And, he said, the lack of uniforms in civilian life is another change that veterans must face.

“Everybody knows their place in the pecking order (in the military). You wear it literally on your shirt sleeves on your shoulder,” Kim said. “You can walk into any setting and even if you do not know anyone—it is the first time meeting everyone—you know your place. ‘That person outranks me. I outrank that person.’ In a civilian setting, it does take time to understand where the pecking order is and where you fall within that pecking order. In some sense, you kind of start from ground zero in terms of establishing credibility. That is a challenge many transitioning veterans face, including me.”

There are ways to deal with that challenge, Patty Horoho, retired U.S. Army lieutenant general said.

“If you are entering a room, you should have done your homework and you should understand who you are meeting,” she said. “Look at the bios. Understand what the person does, so you know who that person is. And you can go to and introduce yourself. Also remember, if you are in a room, you should make eye contact with everybody that is in that room, and you should make everybody that is in the room feel important and valued. And if most of the people in the room are senior to you, you still should convey that same exchange of confidence and respect.

“I have always believed that if you treat everybody with dignity and respect, it does not matter what your rank is or what position someone is in.”

Horoho, who had a 34-year career in the Army, was the first nurse corps officer and the first woman to become surgeon general of the Army. She worked at the Pentagon on 9/11 and provided first aid care to 75 others injured during the attack. She is now CEO of OptumServe, which serves the federal health services business of Optum and UnitedHealth Group.

“Relationships are key to everything,” she said. “There is automatic credibility given with your rank because people know what it takes to earn that particular rank. In the corporate world, there is not instant credibility because you walk in civilian clothes, and nobody knows whether you are the CEO or whether you are a brand-new employee in the organization unless you start building relationships. And once you build relationships, when you are working on a project, people want to be part of that, they want to help once you foster that type of environment.”