The Ins and Outs of Social Media Polarization

By Justin Walker

People can be passionate about their beliefs, especially on social media. However, as people express those feelings through tweets, posts and videos, polarization is evident on nearly every social platform.

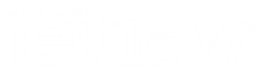

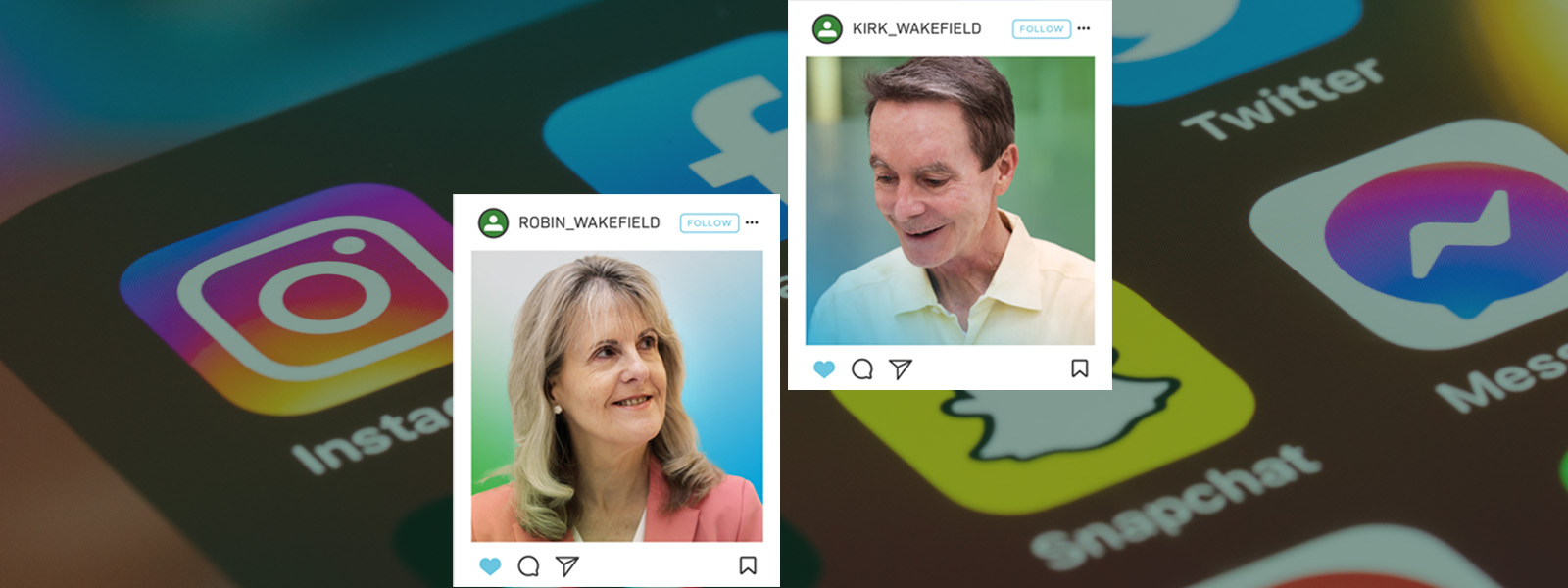

This polarization inspired Robin Wakefield, professor of Information Systems, and Kirk Wakefield, the Edwin W. Streetman Professorship in Retail Marketing, to investigate the motivations and responses to identity groups on social media in the article, “The Antecedents and Consequences of Intergroup Affective Polarization on Social Media,” published in the Information Systems Journal.

“You often hear that we are a polarized society,” Robin Wakefield said. “Ideologically, we are in different groups, and the tendency is to think that groups are against each other, that each intensely dislikes the other.”

Identity groups can exist across various lines, such as politics, religion or sports, Robin Wakefield said. As people interact with others on a particular subject, they form “in” and “out” groups. Affective polarization is the liking for the “in” group compared to dislike for the “out” group.

“Everybody is part of many different types of groups,” she said. “That would be your ‘in’ groups and the ‘out’ groups are those you view as an opposition or rival group.”

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Wakefields noticed polarization along the topic of mask-wearing, especially on Twitter. So, they investigated people’s motivations for expressing their feelings on the platform.

Twitter users were asked to self-identify with their respective political parties and were then shown a set of randomized tweets, including pro- and antimask messages, Kirk Wakefield said. Next, the researchers measured how strongly the users felt toward the various tweets and the groups associated with each post. What they found was a bit surprising for both of them.

“They were not as polarized as you might think,” Kirk Wakefield said.

The issue isn’t that people have disdain for others in the rival group. It’s that highly-identified members of a group think more highly of themselves, which distances them from rival groups. Polarization is more a function of inflated feelings about our own group and less about disliking others. Due to inflated feelings of self-importance, we are more likely to “shut down” the other side by muting, blocking and unfollowing the “out” group.

These findings have implications for both information systems and marketing, the pair said. Understanding how people relate to each other informs us about the norm of relationships on electronic platforms, Robin Wakefield said.

“Greater affective polarization on social media is likely to facilitate group isolation and create echo chambers. Increasing information flow among groups may dampen inflated group biases to decrease polarization,” she said.

As for marketing, Kirk Wakefield sees a connection between consumers’ online and offline behavior.

“How you behave online translates into how you behave in real life,” he said. “You can’t separate those. If you are the kind of person who is abusive online, there’s a strong chance you are like this in real life.”